Matthew 16:13-20

Huston Smith, a renowned historian of religion, once wrote that in the history of the world there are only two individuals whose lives have been so extraordinary that they provoked people to ask not only “Who are you?” but “What are you? What order of being do you belong to?” One was Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, and the other was Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ. And we can certainly see that dynamic in our Gospel today. People struggled to make sense of Jesus, to put him into some category. He was obviously more than just a rabbi or a teacher. Some thought he was a prophet, but even that didn’t seem to suffice. There just were not any pat or easy answers to those questions: Who are you? What are you? And, you know, there still aren’t. There’s a story about a Baptist, a Catholic, and an Episcopalian who died and appeared before the pearly gates of Heaven. Jesus greeted them there and said, “You have to pass an entrance exam, but there’s only one question: Who do you say that I am?” The Baptist immediately stepped forward and confidently asserted, “The Bible says . . .” but Jesus interrupted him: “I know what the Bible says. Who do you say that I am?” The Baptist replied, “Well, I don’t know.” So instantly a trap door opened beneath him and he disappeared. Next, the Catholic stepped forward and began, “The Pope says . . .” but Jesus stopped her: “I don’t care what the Pope says. Who do you say that I am?” And the Catholic stammered, “I don’t know,” and then she fell through the trap door. So then Jesus turned to the Episcopalian and asked, “Who do you say that I am?” And the Episcopalian, looking thoughtful, said, “You are the Christ, the Son of God.” Jesus smiled and was about to open the pearly gates when the Episcopalian continued “but on the other hand . . .”

Peter, at least in this moment of the story, does not equivocate; he does not hedge his bets. Nor does he offer some rote answer to Jesus’ question. According to Matthew, he is the first person to speak from his heart and say, You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God. It is a turning point in the Gospel. Jesus praises him, names him Rocky, and proclaims that this is the kind of faith he will build his church on. And then he utters the most perplexing words in this passage: he orders his disciples not to tell anyone who he is. If the whole point of the Gospel is to make Jesus known, that seems to make no sense. It seems crazy. But if the whole point of the Gospel is to inspire the kind of faith Simon Peter has, then it makes perfect sense. In fact, it’s brilliant and shows there is a method to Jesus’ madness.

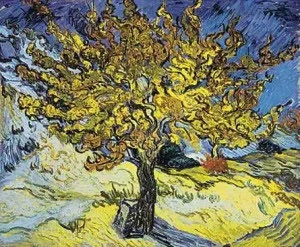

Thinking of how best to convey this, I remember a quotation that one of our church school teachers here used to refer to. It read, “A child is not a vessel to be filled, but a candle to be lit.” There are times, of course, when education does consist primarily of imparting information, filling the vessel, but when we are talking about spiritual formation, that is not the case. True faith is not taught, it is caught. What we try to do in church school is create an environment where children can know the presence of God and experience Jesus Christ, the Son of God. There is no substitute for that kind of encounter, which lights the candle and puts a child into direct contact with the Holy One.

But that’s not just true for children. All of us here could memorize the Nicene Creed and still not have faith. We could know the Prayer Book Catechism by heart, we could read volumes of systematic theology, and still not be able to answer the question Jesus puts to us today, Who do you say that I am? Like Peter, we have to experience that truth ourselves, or to put it better, God has to reveal it to us in a personal way. The Church can point us to it; our families and friends can encourage it; worship can open us up to receive it so that ultimately each one of us can know for ourselves that Jesus is the human face of God, and that in him all the fullness of God is pleased to dwell.

What the New Testament shows is a community, a Church, filled with people who know that, and as a result have been set free and set on fire. As Paul writes in Romans today, they have been transformed by the renewing of their minds. They are empowered by the Spirit of Christ to use their many different gifts in ways that reveal God to the world around them. The early Church did not grow in love, grace, and numbers because they memorized rote phrases about Jesus, the Son of God and made others do the same. The early Church grew in love, grace, and numbers because they experienced Jesus, the Son of God, and helped others do the same. Evangelism in the Church should never involve bullying people into belief, coercing them to accept certain propositions about Jesus or be damned; it should express itself in being a welcoming community where people can catch the faith, experience the Risen Christ, and be changed for the better. One of the most moving letters I ever received came from a parishioner who arrived at the parish wounded and uncertain. Some years later, when she was a strong and active participant in that community, she wrote to me and said, “When I first came to this church, I did not believe that Jesus is alive. Now I do.”

Such faith, like Peter’s faith, is a gift, something not revealed by flesh and blood, but by God. Whatever faith we have, whatever experience of Christ we have, is also a gift. It’s a gift that God wants to give to everyone. And as the Bible indicates, it is a gift that is conveyed, nurtured, and expressed in community. At times our faith may blaze brightly, and at other times it may barely be flickering. But by being here with each other, remaining faithful in prayer and worship, and serving others, we allow God to keep the flame burning and, when necessary, to relight the candle. That way each one of us can know Jesus Christ, the Son of the living God ― not in theory, not second-hand, but for ourselves.